How long after the discovery of chemical contamination in groundwater should the government be checking to see if those chemicals have turned into a gas (“vapor”), and migrated upward to intrude into the breathing space of homes?

They shouldn’t wait a quarter of a century, that’s for sure.

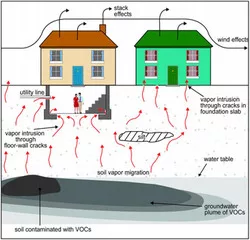

News just broke out of Bellaire, Ohio that the EPA will soon be testing to see if perchloroethylene (PCE), known to be in area groundwater since the 1990s, is intruding in vapor form into overlying homes and businesses. PCE belongs to a family of chemicals known as VOC’s– “volatile organic compounds”–precisely because they convert to gas so readily. PCE, TCE (trichloroethylene), DCE (dichloroethylene) and VC (vinyl chloride) are among the VOC’s which were used by factories beginning more than 100 years ago as industrial cleaners (“degreasers”), and then often recklessly dumped, spilled or buried, and left to bleed down through the soil and into groundwater supplies. PCE was notoriously used and dumped by dry cleaners, which seems to have been the problem in Bellaire.

Most VOC’s are designated as “known”, or at least “possible”, “human carcinogens”. And so they are especially dangerous when they reach the groundwater because communities sometimes draw their drinking water from the ground, and also because–as is the concern in Bellaire–the VOC’s threaten vapor intrusion.

That VOC’s convert to gas has been known for more than 100 years; that VOC’s migrate upward from a plume of VOC-contaminated groundwater has been known for many decades. And so there really is no good reason for the 25-year delay for vapor intrusion testing in Bellaire.

I’ve written many blogs on this topic, but just to summarize: These are the factors that must be considered when a community is deciding whether to test for the possibility of vapor intrusion:

Please note that these are not hard and fast rules. For example, in one of my cases, the VOCs had traveled in groundwater more than 2 miles from the factory where they were originally dumped.

So, being conservative is necessary. “Educated guesses” and “computer modeling” to predict whether chemicals might have traveled in a certain direction or a certain distance are inadequate. They cannot provide the assurance of actual testing. Bottom line: If VOC’s were dumped and left in the environment at a location from which groundwater even possibly flows toward places where human beings live and work, it is urgent that there be testing both for groundwater contamination AND for vapor intrusion.

In other words: Don’t wait 25 years.

http://wtov9.com/news/local/epa-to-start-testing-soil-and-gas-in-bellaire

"*" indicates required fields